Swine Insights International

Today, we’re diving deep into an issue that’s shaping the global pork industry. We’re talking about industry consolidation and its effects, good and bad on the global pork industry. While I’ll be using the U.S. as an example, emerging markets like China and Southeast Asia are following a similar path and would be wise to learn from our experience here in America. So, let’s dissect how this consolidation impacts markets and what lessons can be learned.

Elastic Supply: Flexibility of Small Farms

Prior to the 1990’s, the U.S. pork industry consisted mostly of relatively small farms most of which were diversified operations where the pigs were only one revenue stream along with other livestock and crops. These small-scale operations had the agility and flexibility to adapt to market conditions. When prices were good, farmers could quickly ramp up production. Conversely, if the market was saturated, these small players could easily downsize or temporarily exit the industry waiting for a better opportunity.

This kind of setup allowed for what economists call an “elastic supply.” Think of it as a rubber band; you can stretch it out or let it contract based on the forces applied. Because so many players contributed to the supply, no single entity was crucial. This dispersed risk made the market robust and dynamic.

At the same time, demand was mostly predictable. Domestic per capita pork production has been relatively stable in the US for many decades. Exports were low, in fact, as recently as the early 1990’s, the US was a small net importer of pork. So, we had an elastic supply and a predictable demand. The combination moderated volatility in the markets. Like today, margins were fairly low but so was capital investment and market was relatively low as well.

The Changing Landscape

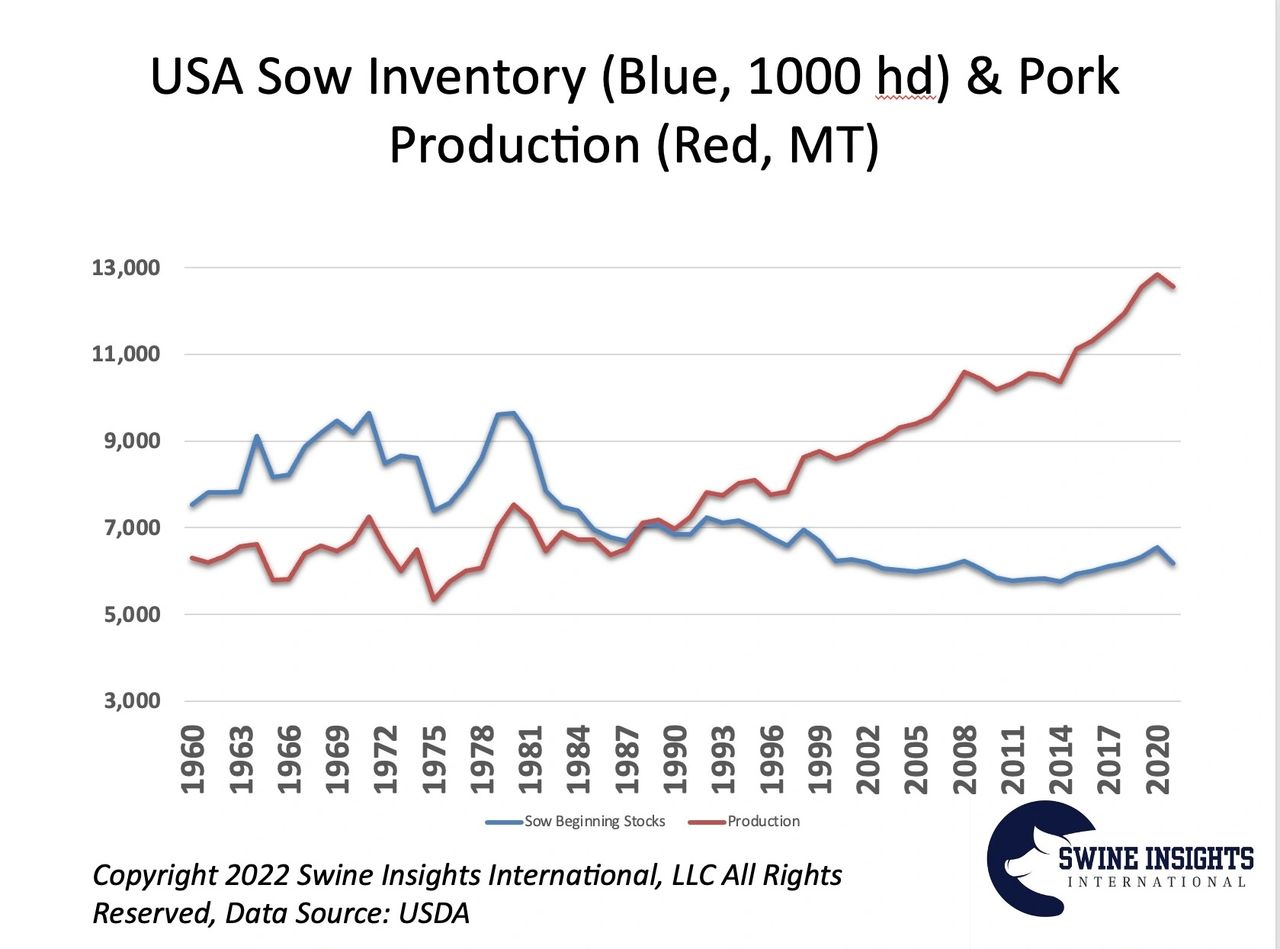

Beginning in the 1990’s, a now familiar pattern began. The industry began to industrialize, and large companies began gaining market share. These new, bigger farms brought rapid improvements in productivity and efficiency. The trends of pork production and sow inventory at the national level which had historically largely tracked together began to diverge. Pork production, measured in metric tons, began to rise steadily and dramatically while the sow inventory stabilized and later began to decline (See Chart 1). We were producing way more pork with the same or even fewer sows. These are all very positive trends of course, but it also brought changes that were not necessarily beneficial.

The Catch: Reduced Elasticity

These larger companies are often highly leveraged, meaning they’ve taken on significant debt to fuel their expansion of large, technologically advanced farms. This financial structure makes it far less feasible for them to cut back operations temporarily when supply outstrips demand. The result is reduced elasticity of the supply chain. Furthermore, the rapidly expanding productivity quickly outstripped the relatively flat domestic demand. Fortunately, the US is one of the most cost-efficient places in the world to raise pigs, so US pork found willing buyers around the world for our excess production and exports soared. The US exported less than 2% of all pork produced in the early 1990’s and by the 2020’s that had grown to almost 30%.

Again, the new markets were a blessing for pork producers, but the U.S. pork industry has become increasingly reliant on exports. When international demand is high, this is fantastic for business. But this relationship has a dark side: volatility. With a less elastic supply and more unpredictable demand, market volatility increased significantly. The new reality was higher highs and lower lows and periods of losses were longer than the past.

In recent years, the U.S. has exported a significant amount of pork to China. When African Swine Fever decimated China’s pig population, U.S. exports soared. However, geopolitical tensions and trade wars can turn this lucrative market into a high-risk venture overnight, affecting the entire supply chain back home. International market demand is very difficult to project. Not only does it involve global economic factors which adds new variables, it also involves non-economic factors like politics and demographics which are difficult, if not impossible, to predict with any reasonable accuracy.

Lessons for Emerging Markets

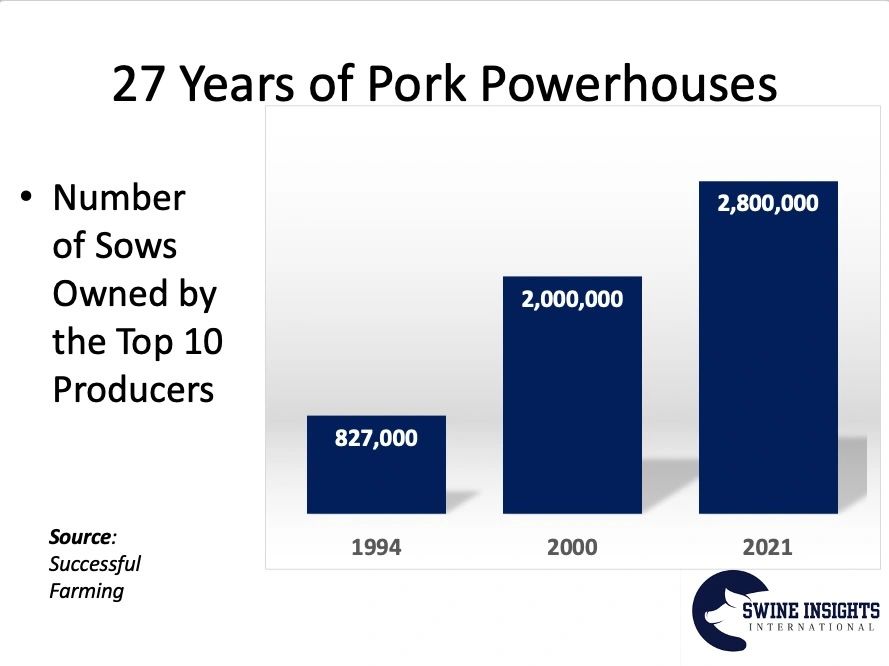

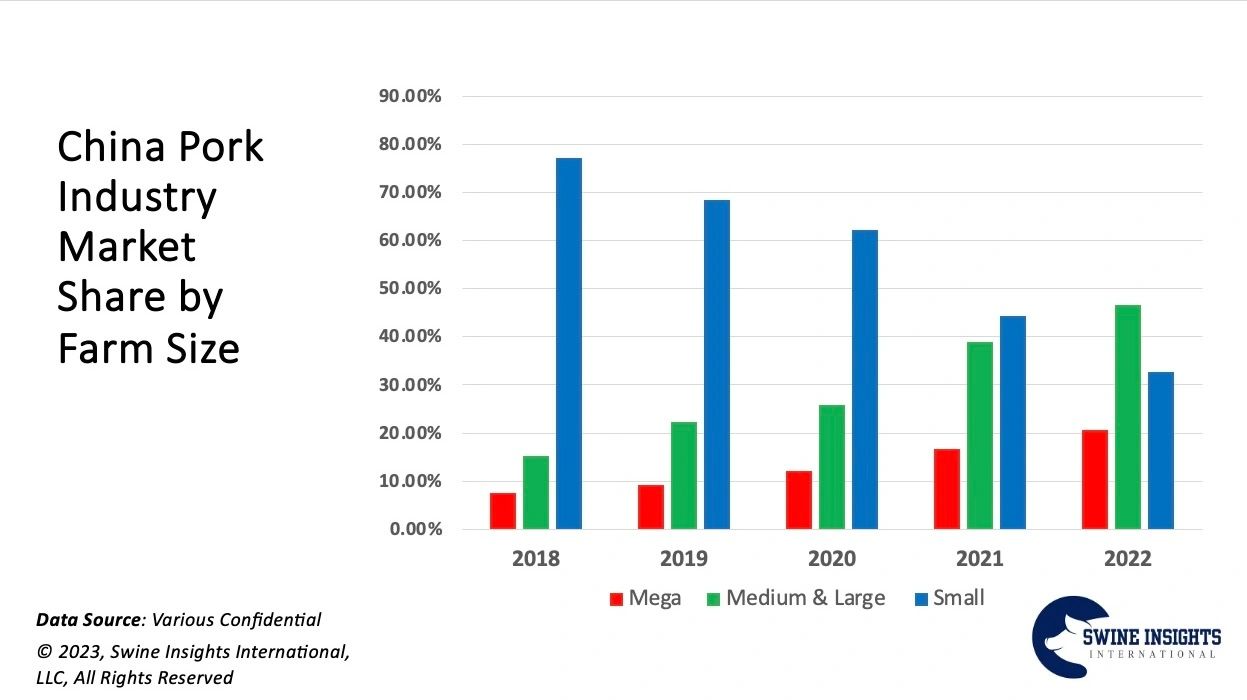

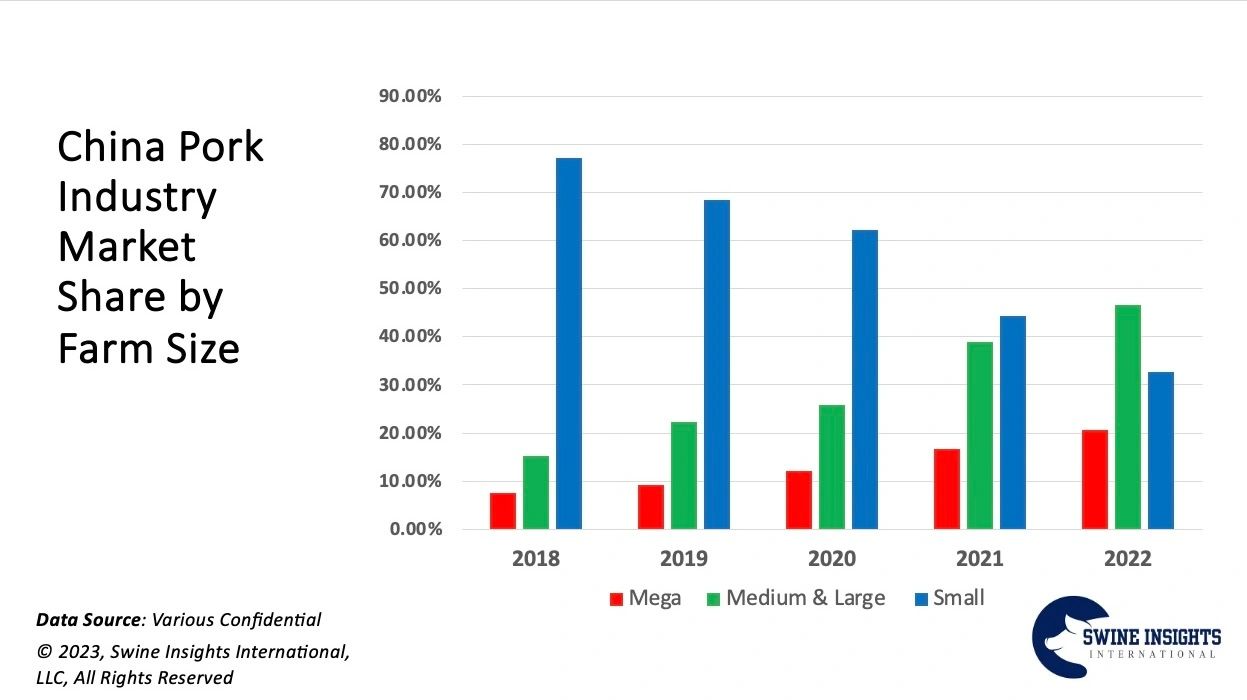

Now, let’s turn our focus to emerging markets. China and to a lesser extent, Southeast Asia, are currently experiencing rapid industry consolidation (See Chart 2). They are seeing levels of consolidation in a matter of just a few years that took over twenty to fully develop in the US and other more mature markets. As they follow in the footsteps of the U.S., they’re also likely to inherit some of the challenges that come with the transitions, such as reduced supply elasticity and increased vulnerability to market conditions.

It’s crucial for emerging markets to strike a balance. On one hand, consolidation can bring about operational efficiencies, improve biosecurity and help meet demands without excessive reliance on imports. On the other, it could lead to a brittle, less responsive supply chain, vulnerable to even minor fluctuations in demand. We’ve already begun to see such challenges emerge in China with long periods of significant losses experienced by an industry and even a few years ago rarely experienced losses at all, much less significant losses.

To further complicate matters, the consolidation has occurred so quickly that they haven’t had time to develop tools and strategies to deal with the new reality. Over the years, the US industry has developed sophisticated risk management strategies and established tools like futures markets, to deal with the volatility. These tools are just now emerging in markets like China and SE Asia and there is a huge education gap. The average Chinese producer, even quite large producers, have only a tenuous grasp of basic hedging strategies, much less more sophisticated approaches to managing volatility. Furthermore, the futures markets, where they exist, are still immature and are volatile themselves as they’re utilized primarily by speculators.

What’s On The Horizon?

I’d speculate that this trend of consolidation will persist unless we see some form of regulatory intervention which is highly unlikely. Industry consolidation isn’t bad, if fact, it’s quite good and necessary in order to improve resilience to animal disease challenges and improve the economic and environmental sustainability of pork production. Like any positive, however, there is also a negative side and producers and policy makers in emerging markets would be wise to learn from our experience in the US.

What Can Be Done?

Industry consolidation isn’t inherently good or bad. It has driven technological innovation and operational efficiencies that small-scale farms could only dream of. However, we must acknowledge the complexities it introduces to the supply chain and market dynamics. A nuanced approach that recognizes the likely increased volatility will be key. Producers should work hard to not only improve operational efficiencies, but to also educated themselves about risk management strategies that can help them manage the inevitable swings. They should also work to secure access to significant capital to survive periods of losses that are likely to be higher and longer.

Policy makers and industry leaders should work to establish the necessary risk management infrastructure to help producers manage input costs and revenue. Food security demands stable production capacity so access to risk management tools, insurance and funding resources will be critical to ensure a stable food supply. Ensuring fair competition should also be a priority or these large organizations can very quickly become too big to fail and require massive government bailouts when losses become too much.

If producers, industry organizations and governments can work closely together, they can ensure that this transition is mostly positive. Learning from more mature industries can help them avoid even greater challenges that are arising from the unprecedented rapidity of industry consolidation.

About the Author: Todd Thurman is an International Swine Management Consultant and Founder of Swine Insights International, LLC. Swine Insights is a US-Based provider of consulting and training services to the global pork industry. To learn more about the company, send an email to info@swineinsights.com or visit the website at www.swineinsights.com. To learn more about Mr. Thurman’s speaking and writing, visit www.toddthurman.me