Research shows that if more piglets are positive for Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (M. hyo) at weaning, there will be more problems in finishers, with decreased average daily gain, increased mortality and poor feed conversion.1 There will be a lower percentage of pigs sent to the primary market as well as higher treatment costs.

The costs of M. hyo can really add up. When actual production numbers from 2007 to 2015 are plugged into an economic model, the cost is $4.99 per pig.2 Data from other farm systems indicate it’s $2.85 per pig.3

To reduce the amount of downstream disease in pigs, we need to reduce the amount of M. hyo shedding. This begins with proper acclimatization of gilts going into the sow herd, which is a challenge.

Negative gilts present challenges

Historically, most replacement gilts were born into positive herds, or they were raised internally in the herd and were infected early in life. They had plenty of time for shedding to minimize before farrowing, which helped keep herds stable for M. hyo. By stable, I mean a low percentage of weaning-age pigs are positive for the pathogen within the respiratory tract.

Today, most replacement gilts are negative for M. hyo and aren’t acclimatized until they get to the sow farm. Therefore, the first challenge is getting them infected within a reasonable time frame.

Gilts need to be brought in at a young enough age so there’s enough time following infection for M. hyo shedding to decline. This is critical whether you want to stabilize a positive sow farm and reduce the impact of clinical disease in the finishing phase or if your goal is herd closure and M. hyo elimination.

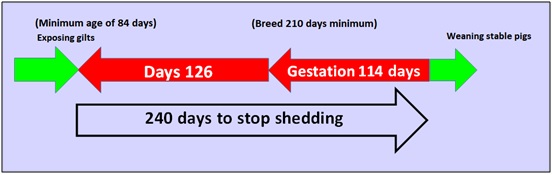

Ideally, negative gilts would be infected by 84 days of age. Figure 1 demonstrates the time needed to reduce shedding in farrowing gilts and their piglets.

Figure 1. Gilt Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae exposure timeline

Gilt-exposure methods

There are several methods of exposing negative gilts:

- Use seeder animals, an approach that’s been utilized in the industry for a long time. It works well if the right animals are used and there’s plenty of time — but it can also be difficult.To achieve a shorter time for infection, such as 30 days, six seeders for every four naïve gilts is needed to be 100% successful. However, if the infection in the seeders dies out, it can be difficult to get the acclimatization program restarted. The result can be problems with M. hyo in finishers and lost performance during the process, and it may take time to re-establish herd stability.

- Intratracheal inoculation is another way to acclimatize naïve gilts and has been explored in the research arena. I wouldn’t recommend this method because it’s labor intensive and it can pose a danger to staff since restraint of gilts is necessary.

- Aerosol inoculation is new technology that’s been used in other species for vaccination and may be a possibility for hyo acclimatization of gilts. It’s less labor intensive than intratracheal inoculation and animals don’t have to be restrained. There are some technical steps required. For example, it has to be done in an area with small air space. If you want to consider this approach, it’s imperative to work with your herd veterinarian so all the technical details are addressed.

One of the keys to successful acclimatization is having a good diagnostic protocol to confirm that gilts have in fact been properly exposed. Toward this end, testing every group of exposed naïve gilts is key, whether your goal is M. hyo herd stabilization or elimination.

Considering elimination?

M. hyo elimination is possible using a combination of herd closure, vaccination of the breeding herd and medicating of the breeding herd as well as piglets. Infected piglets also can be treated individually with an injectable antibiotic to help reduce the impact of the disease.

Elimination is recommended when it becomes a struggle to get gilts exposed on a consistent basis, for herds in a filter project and when producers simply become tired of dealing with costly M. hyo clinical problems.

If you’re considering M. hyo elimination, one of the first questions to ask is whether it really will be worthwhile. This might not be possible for farms located in pig-dense areas where reinfection is a strong possibility. However, when we followed 100 sites in pig-dense areas throughout two seasonal periods, we found only 6% of the sites were positive for M. hyo from lateral-source introduction.

Summing up

Proper gilt acclimatization is key to successful herd stabilization and M. hyo management. This applies whether your goal is to stabilize the herd and minimize the load of M. hyo in weaned pigs or to eliminate M. hyo.

A good diagnostic plan is essential. Every group of gilts that enters the herd must be checked after exposure to ensure proper acclimatization. Unfortunately, it takes time, especially in herds receiving adult replacements. Acclimatization of gilts is also more challenging today because most replacement gilts are M. hyo-negative.

Lateral transmission does occur, but it’s not very frequent. If you are having a problem controlling M. hyo in a herd, it’s likely a problem originating from the source sow herd and not the geographic area.

You’ll have better results managing M. hyo if you work with your herd veterinarian to develop an individualized plan.