When it comes to porcine reproductive and respiratory virus (PRRSV) it’s important for the veterinarian and farm personnel to know the health status of a herd or barn. Today, serum is the “gold standard” for antibody detection; however, it is somewhat inconvenient because collection requires technical skill, time and effort.

Some have dabbled with sampling colostrum and milk to determine PRRSV antibody levels in sows, but the numbers have been limited. Of course, any alternative method will need to provide sampling ease as well as confidence in the results.

“In this study, the objective was to compare the PRRSV antibody detection in serum samples to those detected in fecal samples collected at similar time points,” Sam Baker, veterinary student at Iowa State University, told Pig Health Today. He conducted the study in two phases.1

Study design

The study involved 60 sows nearing parturition from a 6,000-head, PRRSV-positive, stable farm.

In phase 1, Baker collected serum and fecal samples 1 week before the sows farrowed. Based on the serum PRRS ELISA test results, he identified a subset of 15 sows with a low sample-to-positive ratio (S/P ratio) and 15 with a high S/P ratio.

For phase 2, as those 30 sows began to farrow, Baker collected colostrum and feces from each sow within 24 hours. He then collected milk and feces samples from those sows within 72 hours post-farrowing.

“In the statistical analysis, I was looking for an association between milk, serum or colostrum PRRSV antibody levels and fecal antibody levels,” he noted.

The results

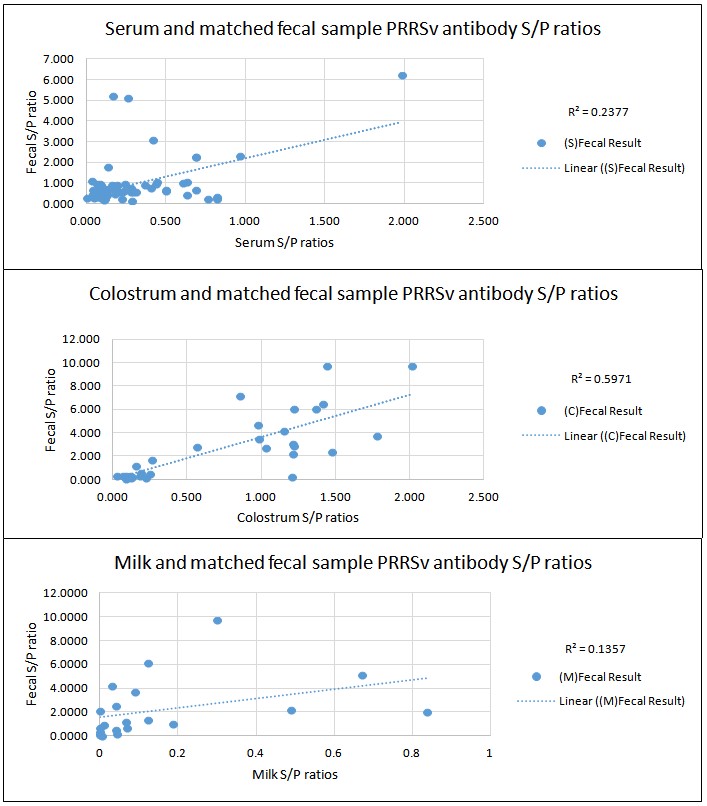

The relationship of PRRSV antibody levels in sow feces, serum, milk and colostrum is reported in the accompanying graphs. Baker offers the following summary:

- PRRSV antibody levels in feces were poorly correlated to levels in pre-farrow sow serum (R2 = 0.238) and early lactation milk samples (R2= 0.138) as measured by ELISA S/P ratios.

- PRRSV antibody levels in feces were moderate to highly correlated in post-farrowing colostrum samples (R2= 0.597) as measured by ELISA S/P ratios.

- Considering only the PRRSV ELISA-positive, pre-farrow serum samples, the PRRSV antibody levels found in fecal samples were moderately correlated (R2= 0.54) to serum-sample levels.

Based on those correlations, Baker concluded that “fecal samples may be an appropriate, easier-to-obtain sample than serum or colostrum” to determine the PRRSV antibody level within a sow herd. “Fecal ELISA testing may provide a more consistent PRRSV antibody S/P ratio than serum-, colostrum- or milk-sample testing,” he added. That’s because the sow’s hydration states, the colostrum/milk production stage and piglet suckling activity can all impact the sample.

Baker noted that additional, larger-scale testing would be beneficial, as would evaluating fecal antibody-sampling prospects for other swine pathogens, such as circovirus.

1 Baker S, et al. A comparison of sow fecal PRRS antibody levels to PRRS antibody levels measured in serum, colostrum or milk samples. Student Research Posters. Am Assoc. Swine Vet Annual Meeting. 2020;220.